Author’s Note: After two years of budget travel through fifteen Asia-Pacific countries and a wonderful visit to the USA – hosted all along the way by local and national YMCAs, I had settled high in the rugged, jungle-clad mountains along the Burmese border in the extreme north of Thailand. The journey to this remote outpost was like living the most wonderful dream — my thoughts drifted back to warm lagoons, smiling faces, and many friends in grand reunion – yet, with a breaking heart, as happy reunions ended all too soon. But soon after my arrival — while carrying out the body of one of our patients who died of Malaria — it came as a stark realization that providing rural health care with no electricity or running water was going to be a bit different from my earlier YMCA experiences!

In June 1988, I joined an American aid agency on a cooperative project with the Royal Thai Government Ministry of Public Health to help establish and maintain a system of comprehensive health services for 20,000-30,000 highland residents of an isolated, undeveloped, politically unstable and insecure region along the Thai-Burma border in the extreme north of the country.

In addition, to operating a small in-patient/ out-patient facility staffed by area residents from all the major ethnic groups, the Project provided health worker training, supervision, public health services and community development in the local ethnic minority villages.

Our hospital had been built by the infamous Burmese Opium Warlord, Khun Sa, to support the Shan United Revolutionary Army’s struggle for a separate, breakaway Shan State, independent from Rangoon. They were eventually forced from their stronghold in our village, and back into Burma following an intense land and air assault by the Thai military. However, ongoing skirmishes between rival drug warlords could still be heard just across the border as they flung mortars at each other to control the narcotics trading route that ran through our village.

Our district was also part of an area known as the Golden Triangle, that sprawls over the common borders of Thailand, Burma and Laos, and contains some of the world’s largest expanses of opium under cultivation.

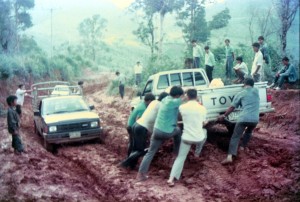

In this generally lawless ‘no man’s land’, one could never be certain about the security situation, which at best was not good, with violent deaths and many injuries occurring locally. The only road from our village to the lowland was unsealed and dangerous, with steep muddy inclines and unprotected drop-offs into the valleys below. But the villagers kept the bamboo along the road cut back to reduce the chances of ambush – whether for robbery or murder.

Widespread poverty, malnutrition, malaria, tuberculosis, parasites, anemia, and opium addiction were common problems. The birth rate in our area was twice that of Thailand as a whole; the death rate almost four times as high. Maternal and child health programs, communicable diseases control, family planning and hospital services were inaccessible to these highlanders because they were too far and difficult to get to, and the significant language and cultural barriers between lowland Thai health care providers and highland consumers.

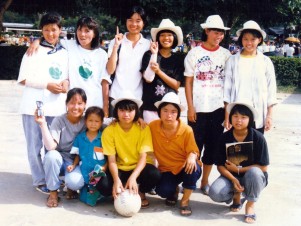

Most of our 43 Highland Health Center staff were members of local ethnic groups, known as ‘hill tribes’, who had received Project training and continuing education as medical assistants, health technicians, and community health workers. We had six nurses (three Burmese and three Thai) along with three American medical personnel who rotated through on six-monthly contracts, and a full-time American Project Director.

Nine different languages were spoken at our health center, which consisted of in-patient and out-patient care facilities, medication dispensary, laboratory services, administration and training facilities, kitchen and staff housing.

Electricity came in during my second year there. Up until then, we used kerosene lanterns and could contact the District Hospital in the lowland on a two-way radio powered by the battery of our hospital truck, which also served as an ambulance and supply vehicle to transport medicines and patients up and down the mountain.

In the rainy season, we were often totally isolated because the road was impassible, and most local drivers refused to take severely ill patients if they thought the patient would die in the truck – which they believed would hex the truck, and therefore his business. At times, patients had to be physically carried down the 13 km of steep, slick mud to the main road.

Thai language training was provided to all staff as the bridging language at the health center. For example, general staff meetings were all conducted in Thai language. Translators were also employed to assist communication with patients from the various ethnic groups.

It was a wonderful international and intercultural mix. Indeed, the surrounding area seemed more like rural China and Burma than Thailand. In many ways, it was like running a summer camp – nights lit by serene lamplight, a fun, youthful staff, with lively parties, singalongs and creative variety shows.

Most of our staff were ‘stateless’ border residents without formal Thai residence or refugee status, and therefore ineligible to complete the Thai educational requirements to enter MOPH health worker positions or training programs. Therefore, the Project also offered Thai high school classes as a basis for employment as civil servant health workers when the Thai Government assumed total responsibility for the Project in 1991.

Stay tuned for “The Warlord’s Hospital (Part Two)” – coming soon!

You can read more about Jim’s backstory, here and here.