Over the years I have written hundreds of articles about our American heroes but very few about our allies heroes. The Battle of Long Tan is a story I am proud to share with those who read my articles about American heroes. The brave men who fought the battle at Long Tan is a story about 108 Australians who demonstrated what true grit is,

Late afternoon August 18, 1966 South Vietnam for three and a half hours, in the pouring rain, amid the mud and shattered trees of a rubber plantation called Long Tan, Major Harry Smith and his dispersed company of 108 young and mostly inexperienced Australian and New Zealand soldiers are fighting for their lives, holding off an overwhelming enemy force of 2,500 battle-hardened Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers.

With their ammunition running out, their casualties mounting and the enemy massing for a final assault each man begins to search for his own answer and the strength to triumph over an uncertain future with honor, decency and courage.

With their ammunition running out, their casualties mounting and the enemy massing for a final assault each man begins to search for his own answer and the strength to triumph over an uncertain future with honor, decency and courage.

The ensuing Battle of Long Tan becomes one of the most savage and decisive engagements in ANZAC history, earning both the United States and South Vietnamese Presidential Unit Citations for gallantry along with many individual awards. But sadly not before 18 Australians and more than 500 enemy are killed.

Heroism, tragedy and the sacrifice of battle, Long Tan is a grueling and dramatic exploration of war with all its horror that rightly takes its place alongside other legendary ANZAC battles and campaigns such as Gallipoli, Beersheba, Kokoda, Tobruk, Kapyong, Balmoral, Coral and many others.

In May 1966 the first soldiers of the 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) arrived in South Vietnam; the rest followed in June. Within two months, elements of the battalion found themselves engaged in one of the largest battles fought by Australians in the Vietnam War.

By August 1966, the Australian task force base at Nui Dat was only three months old. Concerned at the establishment of such a strong presence in their midst, the Viet Cong determined to inflict an early defeat on the Australians. In the days before the battle, radio signals indicated the presence of strong Viet Cong forces within 5 kilometers of the base but patrols found nothing.

The catalyst for the battle was the VC (Viet Cong, an abbreviation for Vietnamese Communist) attack on the Australian operational base of Nui Dat, located in the center of Phuoc Tuy. The attack occurred during the early hours of 17 August 1966, with the VC using mortars and recoilless rifles.

The Australians had only recently established the base at Nui Dat, from which they sought to operate and assert control of Phuoc Tuy, the province for which Australia had operational authority. While the attack caused only limited damage, it perturbed the Australian Task Force Commander, Brigadier Oliver Jackson, as he recognised the base’s potential vulnerability to a significant VC attack.

In response to the attack, B Company, 6th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (6RAR) was directed to patrol from the base to locate the VC’s firing positions. B Company achieved this task, before being replaced by D Company, 6RAR at midday on 18 August. D Company followed parallel cart tracks leading away from the firing positions into a rubber plantation towards the abandoned village of Long Tan.

It was in this rubber plantation, approximately 4 kilometers to the east of Nui Dat, that the battle took place. As D Company moved through the rubber plantation (with two platoons up and one platoon moving behind), 11 Platoon commanded by Lieutenant Gordon Sharp on the Australian right ran into a small group of VC. After a short exchange, the enemy fled eastwards with 11 Platoon in pursuit.

Little did the Australians know that they were about to collide with a major concentration of enemy forces. Just after 4.00 pm during the chase, 11 Platoon was forced to the ground after coming under heavy fire. Lieutenant Geoff Kendall leading 10 Platoon (in the front left position) was ordered to move to 11 Platoon’s assistance; however, his platoon was also stopped by equally intense fire before it could provide that help. Behind D Company’s two forward platoons, the company commander, Major Harry Smith, with 12 Platoon and Company Headquarters, sent reports to Nui Dat requesting support for his beleaguered company.

From the battle’s outset, the skies opened and an intense afternoon storm added to the cacophony of noise and terror in the rubber plantation. Adding to general chaos in the plantation was the rise of ‘mud mist’, which reduced visibility and made it difficult for both sides to visually identify targets. This phenomenon was common during the Vietnam War, when monsoonal rains fell with such force that the churned red earth below splashed up to 50 centimeters off the ground, staining all that it came into contact with. Further complicating the desperate situation was the loss of comms, with the radios for both 10 and 11 platoons damaged by gunfire.

With 10 Platoon unable to reach 11 Platoon, Lieutenant Kendall was ordered to withdraw his platoon and re-join Company Headquarters. At this point, Lieutenant David Sabben was ordered to swing two sections from his 12 Platoon in a southerly attempt to reach 11 Platoon from a different direction. En route, Sabben’s group also encountered stiff resistance and could not reach their target.

Thus D Company was now splintered into separate groups, each harassed by determined VC attacks. 11 Platoon’s predicament was the most dire. Isolated from the remainder of the company for an hour and a half since first contact, more than half the platoon’s strength of 28 men had been wounded within 20 minutes of the first exchange of fire.

Back at Nui Dat, the Australian base buzzed as reports from Long Tan kept increasing the estimated number of VC opposing the Australians. Allied artillery was already firing on the VC, with targets identified by Forward Observers embedded with D Company. US air support was requested with the Americans enthusiastically agreeing to help.

However, when three F4 Phantom jets responded, they could not identify targets on the ground through the thick cloud, and dropped their ordnance beyond the range of the enemy. Two daring RAAF pilots from 9 Squadron had more luck when they flew through atrocious weather to drop boxes of ammunition from treetop height down to D Company whose supply was alarmingly low.

Later in the afternoon, a relief force was arranged to move to D Company’s aid. First, B Company (which was returning to Nui Dat after their earlier mission) was ordered to turn around and find D Company. Second, permission was granted for the Armoured Personnel Carriers (APC) of 3 APC Troop to move to support D Company. Subsequently ten APC’s left Nui Dat carrying A Company, 6RAR. En route, the APCs had a minor encounter with a group of VC that were attempting to flank the Australians. After a small skirmish, the troops remounted and the APCs sped on towards Long Tan.

Just before 6.00 pm, the surviving 13 members of 11 Platoon were finally able to pull back from their position and make their way to 12 Platoon guided by a smoke grenade. Half an hour later, taking advantage of a temporary lull in the fighting, the combined 11 and 12 Platoon were able to regroup with the rest of the company, consolidating the strength of D Company for the first time in the battle.

The following half an hour saw relentless wave attacks on D Company. Fortunately for the Australians, the ground they occupied fell away slightly at their rear, which afforded some protection from the rifle and machine gun fire which mostly passed safely over their heads. The VC attacks were determined, with their courage proven by their willingness to continue the attack even as large numbers of their own troops fell.

As darkness fell over the rubber plantation at 7pm, D Company’s relief appeared with the simultaneous arrival of B Company and the APCs, their .50 calibre heavy machine guns blasting through the rubber, breaking up the attacking ranks of VC and sending them scattered into the darkness. The Battle of Long Tan was over.

With the battle’s conclusion, and despite the desire of some D Company members to immediately return to 11 Platoon’s location, Lieutenant Colonel Colin Townsend, the (Commanding Officer of 6RAR whom arrived with the APCs), made the decision to pull the Australians back to the western edge of the rubber plantation, where priority of effort was devoted to the evacuation of wounded. The Australians were despondent, believing they had suffered a terrible defeat. However, over the following days, the outcome of the battle crystallised. In short, an Australian infantry company of 108 men had survived an unexpected encounter with two VC formations – later identified as 275 VC Main Force Regiment and D445 Battalion – from which as many as 1,000 probably came into contact with the Australians.

It is essential to note that despite the ten-to-one numerical superiority enjoyed by the VC, the Australians had a considerable advantage of their own – the fire support of three batteries of 1 Field Regiment sited at Nui Dat, complemented by a battery of American medium artillery from 2/35th Artillery Battalion. The Allied soldiers manning these guns worked tirelessly during the battle, firing almost 3,500 rounds.

Townsend estimated that at least 50 percent of the VC dead were killed by artillery fire; however, ascertaining an accurate figure was almost impossible because the volume of shellfire devastated the battleground, making it impossible to determine the cause of death for many of the bodies. The arrival of B Company 6RAR and 3 APC Troop brought an armoured advantage not available to the VC. Combined with artillery support and aerial resupply, this superiority in mobility and firepower offset some of the numerical disadvantage that D Company faced.

Praise for D Company came from many quarters. Prime Minister Harold Holt congratulated the ‘skill, effectiveness and high courage’ of the combatants, which he noted was in the best Australian tradition. American General William Westmoreland congratulated the Australians, declaring they had won one of the most spectacular victories in Vietnam to date.

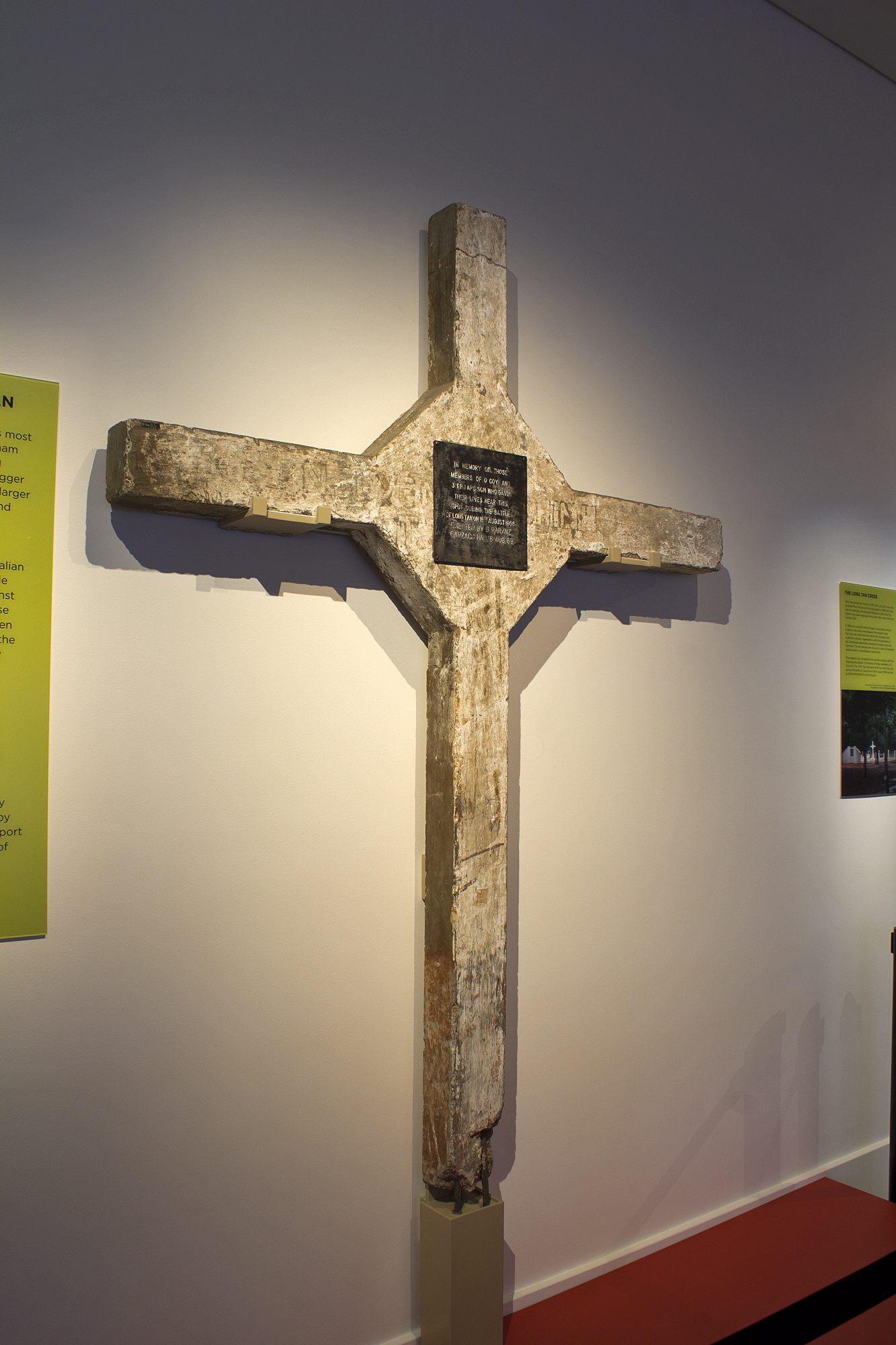

Australia’s actual casualties were 18 killed and 24 wounded. Although that number exceeded any other single day loss in the Vietnam War, the number could have been much higher given the disparity in troop numbers between the two sides. Long Tan is now remembered as an exemplar of Australian soldiers channelling the same attributes of bravery, teamwork and endurance that their forbears displayed in earlier conflicts.

50th Anniversary

On 18 August 2016 a low-key ceremony was held on the site of the battle; more than 1,000 Australian veterans and their families travelled to Vietnam to participate in the 50th anniversary commemoration.In Australia hundreds attended the Australian War Memorial and Vietnam Forces National Memorial in Canberra. Commemorations were also held at Sydney’s Cenotaph, Brisbane’s ANZAC Square, Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembranceand elsewhere. The events in Canberra included: a four-gun salute, a flyover by Vietnam era aircraft: ‘Huey’ helicopters; Hercules and Caribou transports; B-52 bombers.[259] A Last Post Ceremony was held at the War Memorial, read by Mark Donaldson VC.

My heartfelt thanks to Lt.Col Harry Smith (Ret) who helped me to gather the facts to prepare this article.

Top Photo: Long Tan action, Vietnam, 18 August 1966 by Bruce Fletcher (1970, oil on canvas, 152 x 175 cm). AWM Caption: A reconstruction of the Battle of Long Tan, Vietnam, 18 August 1966, between ‘D’ Company and Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army forces; several events that happened at intervals during the battle are shown here happening simultaneously.

All photos courtesy of Wikipedia