By Jeffrey Young – WASHINGTON — Charges of corruption can be a useful political weapon. Accusations of malfeasance, or claims that politicians are not taking effective action against corruption, can weaken or cripple them. This has been seen in a number of nations.

The current investigation of China’s former domestic security chief, Zhou Yongkang, is seen by many as President Xi Jinping’s move to neutralize him as a political rival. A drive to pressure Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to adopt a series of anti-corruption reforms has implications for Erdogan’s Justice and Development party in major elections there later this year. And not long ago, Italy was repeatedly rocked by corruption scandals during Silvio Berluscone’s time as PM, diminishing him.

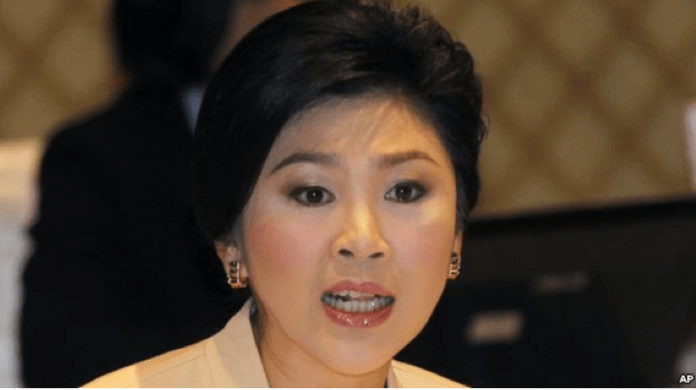

Another example is Thailand, which is in the midst of a crisis involving both politics and corruption. Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, who took office in 2011, is being charged by Thailand’s National Anti-Corruption Commission with improperly running the country’s rice subsidy program. These charges, which the PM denies, and similar ones against other members of her Pheu Thai party, could impact the result of elections held on February 2 that continued their hold on the government.

The streets of Thailand’s capital, Bangkok, have been bloodied in recent days as clashes between Yingluck Shinawatra’s opponents and the authorities have caused at least four fatalities. The protests are largely driven by younger, urban, middle-class, educated Thais who see the rice subsidy program as a corrupt vote buying scheme. The demonstrators want her and her party removed from power.

The rice subsidies began in 2011 when Yingluck became PM. The intention was to buy rice from Thai producers at up to 50% more than its market value and warehouse it to create an artificial supply limit that would drive up the grain’s price. It didn’t work. Other countries stepped forward with their rice to fill the gap, so the worldwide price didn’t rise as planned. The Wall Street Journal reported that the program cost the government up to $8 billion, money hard to generate in financial markets because of Thailand’s instabilities.

But the protests are about more than rice. They’re about the perception that both Yingluck, and her brother, former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, have pillaged the country to maintain themselves in power.

These protests exploded last November when her party introduced a parliamentary measure that would have nullified the conviction and two year prison sentence given in 2008 to her brother, former PM Thaksin Shinawatra. He held that office from 2001 until he was ousted in a 2006 military coup and fled the country.

“Thaksin’s government, and now Yinglucks,” Center for Strategic and International Studies analyst Gregory Poling told VOA, “are viewed by opponents as the most corrupt in Thailand’s history.” Poling adds “So, when they charge Yingluck with failing to prevent state losses through the controversial rice buying scheme, they do legitimately believe they are battling corruption – both direct corruption by officials in charge of the rice purchases, and what they see as corruption in a larger sense through the use of costly state handouts to buy the support of rural voters.”

Thailand’s corruption level, according to Washington-based watchdog group Global Financial Integrity, rose significantly over recent years. GFI’s Brian LeBlanc told VOA that “Thailand’s Illicit Financial Flows (IFF) to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio more than doubled over a decade, leaping from 3.9% in 2002 to 8.4% in 2011. This, compared to an average 4% gain for all developing countries during that period.

Another metric is equally troubling. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. In 2012, the anti-corruption group said Thailand ranked 88th on its scale of 177 nations. One year later, the 2013 index showed a precipitous drop to 102.

CSIS analyst Poling tells VOA that Thailand’s National Anti-Corruption Commission is not only pursuing charges against the PM, but also many members of her Pheu Thai party. This could have significant implications, because if convicted, these lawmakers would be banned from office for five years. And, as Poling notes, that “would effectively negate those [February 2] elections.”

The NACC, while part of the government, says it is strongly independent of political parties and pressure. Former NACC commissioner Medhi Krongkaew told VOA “You can see that we have complaints from both sides of political conflicts. For example, both Abhisit (a Democrat Party leader and a former prime minister) and Yingluck are under our investigations on various charges.” He underscored the validity of the NACC’s actions and its neutrality by saying “We cannot be used as a weapon against any person, if there is no evidence to support the indictment.”

As demonstrations continue to impact Thailand and its government, there is a parallel effort underway to channel the energy of these protestors, and others, for constructive change. The United Nations Development Program has sponsored the Thai Youth Anti-Corruption Network, which says it has more than 3,500 students from more than 90 universities in its ranks. One of its slogans is “Refuse to be corrupt!”

It’s an uphill climb away from corruption in Thailand.

While the youth group presses aggressively for transparency and accountability, it also works against a broadly held acceptance of corruption in the country. The TYACN cites a June 2012 public survey in which more than 63 percent of Thais polled said corruption in government is acceptable so long as they benefit from it.